2 November 2020, Iris Proff

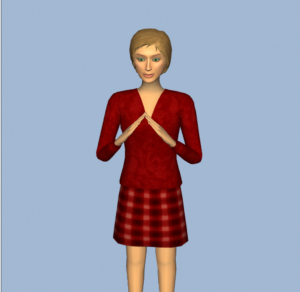

Closing the hand in front of the face is the sign for understand in Sign Language of the Netherlands. © Arco Mul

Floris Roelofsen is a linguist and has spent much of his career investigating the semantics of spoken languages. But when his daughter was born five years ago, his view on language was about to change radically. Soon after her birth it became clear that she was deaf and would never be able to fully access any spoken language.

For Floris and his partner this meant they had to learn sign language as fast as possible. “In terms of grammar, Sign Language of the Netherlands is very different from Dutch. It’s much harder to learn than English, Spanish or French – it’s more like learning Mandarin”, Floris remembers. Yet, there was no time to waste. While struggling to learn this new form of communication, they simultaneously had to teach it to their young daughter.

Learning to communicate in sign language was an eye-opening experience for Floris. As a father of a deaf child, he recognized the challenges and perils deaf children face as they grow up. And as a linguist, he became aware of the unique opportunity sign language offers to understand human language in general.

“My daughter is severely handicapped in a spoken language environment. But in a sign language environment, she is not handicapped at all.”

– Floris Roelofsen –

The Netherlands has a new official language

Since October 13th, Dutch Sign language is an official language of the Netherlands. This means, for instance, that there must now be a sign language interpreter at important speeches by members of the Dutch parliament. This is an empowering step for deaf people in the Netherlands. However, Floris thinks that the new law does not yet tackle the core of the problem. “It leaves children out of the picture”, he states. “They don’t have any language to begin with. A sign language interpreter doesn’t help them!”

More than 95 percent of deaf children have hearing parents, who don’t know sign language when their child is born. These parents face a big challenge: learning sign language is difficult, time intensive and expensive. Sign language courses are scarce, as are opportunities to practice outside of the classroom, and health insurance coverage of sign language courses is very limited in the Netherlands.

The result is that only a fraction of parents with a deaf child learn to communicate in sign language. Hence, in their first years, which are so crucial to their development, many deaf children have very limited language input. Recently, neuroscientists have uncovered the devastating effects of this so-called language deprivation.

Growing up without language

The human brain has specialized regions dedicated to processing language, which are located in the left hemisphere of the brain. Interestingly, in native signers, sign language is processed in the very same regions. Our brains identify language not by the modality through which it is expressed – visual or auditory – but rather by its structural properties and its function for communication.

A 2011 study by a team at UC San Diego and McGill University investigated whether sign language is processed differently by deaf people who learned it from birth and by those who acquired it only later in childhood or as teenagers. The researchers found that in late learners, sign language evokes less activity in language regions, but more in the visual parts of the brain. In the absence of language input early in life, the brain does not develop specialized language regions. This impacts language skills throughout life, including reading and writing abilities.

But it doesn’t end there. Without accessible language input in early childhood, deaf individuals are likely to develop problems with other cognitive and social skills as well. In 2017, every second deaf person in the US was unemployed. In a national survey in Norway in 2008, 20 percent of deaf people stated they felt hopeless – opposed to only four percent of hearing people. Mental health problems, social isolation and cognitive delay are no necessary consequences of hearing loss. Scientists rather believe they are the effects of language deprivation in early life, which could be avoided by providing deaf children access to sign language from birth.

Machine translation for sign languages

Having gone through the challenging process of learning sign language himself, Floris decided to investigate how to make it easier for others. For Sign Language of the Netherlands, there is an online video dictionary providing translations of individual signs. But this does not explain how signs are put together to form sentences. With a group of students at the ILLC, Floris has started to develop a machine translation system that translates sentences from written language into sign language and visualizes these translations with an animated avatar.

A first step towards this big goal is a mini-version of such a translation system, specifically made for deaf COVID-19 patients in hospitals. This group of people, though small, faces major issues: sign language interpreters are not allowed in hospitals in times of COVID-19, reading skills of deaf individuals are often limited and face masks make lip reading impossible. To help them cope, Floris and his team are developing a tool that translates common sentences from the hospital setting into sign language.

The deaf community in the Netherlands

- There are around 15 000 deaf people in the Netherlands.

- More than 95 percent of deaf children have hearing parents.

- There are 5 special schools for deaf children in the Netherlands – in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Groningen, Arnhem, and Zoetermeer.

Sign language opens opportunities for linguistics

Next to these practical goals, Floris has also developed a strong scientific interest in sign language. One of the reasons why sign languages are interesting to linguists is that – unlike spoken languages – they make explicit use of space. Consider this sentence: Sue invited Anna for dinner. She proposed to meet on Monday. In spoken language, the word she could refer either to Sue or Anna. A signing person however can resolve this ambiguity: they will place Sue and Anna at two points in space and explicitly refer to one of them by pointing to her location. Thus, the spatial nature of sign languages enables linguists to study aspects of reference-making that cannot be studied in spoken languages.

Floris emphasizes that, while scientific interest in sign languages is clearly growing, it is still a relatively small and young subfield of linguistics. “There are many open questions yet to be addressed and many further discoveries to be made.”

Curious for more on the topic? Check out this article by NH Nieuws, listen to an interview with Floris Roelofsen by Radio 1 here or read this interview on Van Horen Zeggen, a platform for care and education for the deaf and hearing impaired (all in Dutch).