02 July 2021, Iris Proff

© Iris Proff

Logic is what makes your computer work and it is the scaffold of any scientific discipline. Clearly, logic matters – but does formal logic describe how we solve problems in our daily lives? Are we evaluating logical formulas in our heads when we decide who to vote for, which job to apply for, or which route to take to the supermarket?

There are many hints that we don’t. Human reasoning is imperfect, messy, inconsistent. Therefore, logicians often consider empirical findings irrelevant for their studies. However, the reasoning mistakes humans make are not arbitrary, but very systematic. Slowly, logicians are starting to recognize that the realm of human reasoning can teach us many things about logic – and vice versa.

Anthi Solaki is one of them; she recently completed her PhD at the ILLC, during which she bridged the distinct worlds of formal logic and psychology of reasoning. “I am making logical models more realistic by taking into account human limitations,” she says.

But where exactly do those limitations lie?

The mother of reasoning tasks

Whoever took a course in basic logic can confirm: filling in truth tables, juggling with logical formulas and drawing Venn diagrams are skills we can learn – but they do not intuitively match our everyday-reasoning. In real life, people fall for all kinds of logical fallacies. Someone who believes to be “on a run” when playing roulette falls prey to the “gamblers fallacy”. Election campaigns are often the scene of “ad hominem fallacies” where one side attacks a personal feature of their opponent instead of their argument. And when you slightly misinterpret what your opponent said to have a better ground for your attack, you are making use of the “strawman fallacy”.

People even struggle to implement basic logical rules. This was famously demonstrated by the Wason Selection Task, first developed by Peter Cathcart Wason in the 1960s.

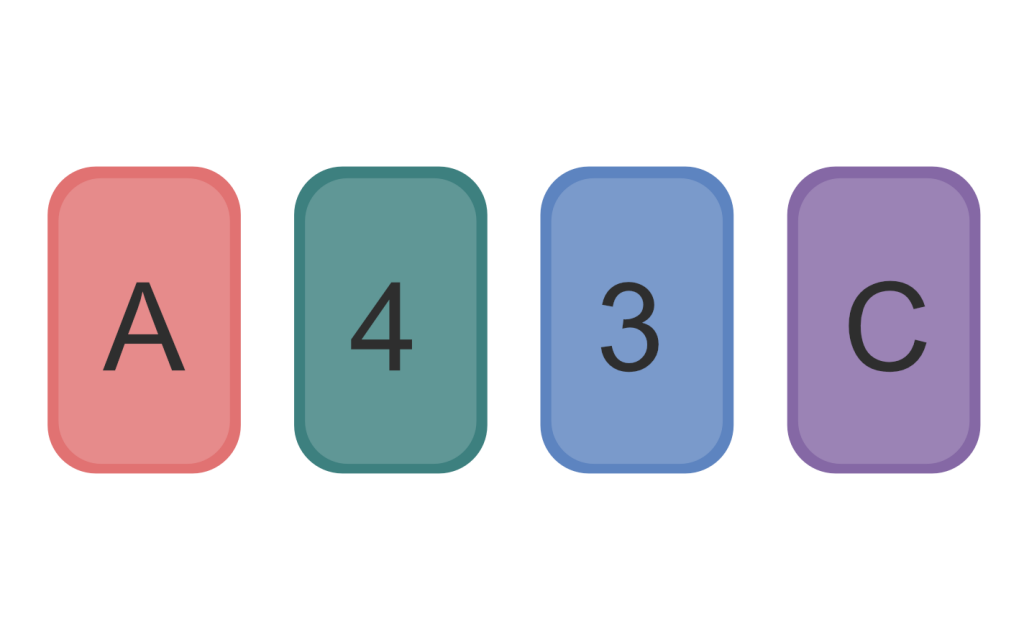

The Wason Selection Task

Consider these four cards. Each card has a number on one side and a letter on the other. Which cards do you have to turn around to check whether the following rule holds: if a card has a vowel on one side, then it has an even number on the other?

To get the puzzle right, a reasoner must apply two logical rules. She needs to check the card with the vowel to confirm that there is an even number on the other side, which is intuitive to most. But she also needs to check the card with the uneven number to confirm that there is no vowel on the other side, which proves to be a harder reasoning step. 90% of people get the answer wrong.

Interestingly, later experiments showed that when the same task is phrased within a familiar context, people perform much better. This is especially true when they need to reason about who might be violating a social rule. These findings gave rise to a heated debate in the field: How do humans reason? And why are some forms of reasoning harder than others?

Inside a reasoner’s head

“There are different schools of thought in psychology about how people reason,” says Anthi Solaki. Some psychologists argue that people represent content-independent, logical rules in their minds which they apply when solving a reasoning problem. Others argue that people only learn statistical patterns from experience. Think about how you can probably not spell out all the grammatical rules of your native language, while being perfectly able to apply those rules in practice. Again others claim that our reasoning ability evolved specifically in contexts in which it is adaptive – such as detecting that someone is breaking a social rule.

Finally, dual process theories propose that humans can do both: They can solve problems automatically using patterns and biases they learned from experience. And they can solve problems by applying abstract rules – but this process is effortful; it costs time and working memory. Depending on how hard a problem seems, how much time is available and how much is at stake, a reasoner can choose between these two reasoning modes.

Should logic care about psychology?

The question if humans are able to reason according to abstract rules is at the heart of the so-called Rationality Debate. Kant, Bolzano and Frege argued that human reasoning with all its biases and flaws cannot tell us anything about the correct way to reason. According to their “anti-psychologistic” stance, the study of logic should be not bothered with empirical findings. This dogmatic conviction created a strict separation between research in logic and psychology. But there is a case to be made against this separation. In a paper from 2008, the logician and co-founder of our institute Johan van Benthem poetically raises the question:

“Do the empirical facts about human reasoning matter to logic, or should we just study relationships between proof patterns, and the armies of them that we call formal systems, in some eternal realm where the sun of Pure Reason never sets?”

Logic and psychology of reasoning certainly serve different purposes, van Benthem says. Logic aims to develop normative rules – how we should reason – while psychology describes how we do in fact reason. Still, van Benthem argues that logic can inspire interesting psychological experiments and that findings from psychology can inspire research in formal logic. He concludes: “If logical theory were totally disjoint from actual reasoning, it would be no use at all, for whatever purpose!”

Epistemic logic and the imperfections of human reasoners

Epistemic logic formally describes the knowledge and belief states of agents and how these can evolve. It certainly is concerned with the reasoning of humans, rather than remaining in what van Benthem called the “eternal realm of Pure Reason”. Still, models of epistemic logic make assumptions that real human agents cannot live up to, argues Anthi Solaki:

- First, they assume that agents are logically omniscient. Every agent immediately knows everything she could theoretically deduce from what she knows. In practice that would have absurd consequences: A student being told the axioms of set theory should immediately know all the answers to all the problems of the field.

- Second, they assume that agents have perfect introspection – that every agent exactly knows what she knows and believes and what she does not know and not believe. However, this is questionable: People often hold implicit beliefs, such as racist or sexist beliefs. They might unconsciously generalize knowledge from one domain to another or falsely believe they know something when they actually don’t.

- Finally, they assume that agents have unlimited theory of mind. By the age of four or five, most children have acquired basic theory of mind. They understand that other people’s beliefs might not match their own: “My mother thinks that my brother broke the vase, but I know that he didn’t”. As adults, we are supposed to have mastered fourth-level theory of mind: “My brother thinks that my mother thinks that my sister thinks that I think that my father broke the vase.” If this sentence gives you headaches, you might agree with Solaki who thinks that humans typically do not reason that deeply about others.

Logical models define how humans ought to reason. But we should make sure that ‘ought‘ implies ‘can‘.

– Anthi Solaki –

Reasoning skills don’t come for free

During her PhD, Anthi Solaki devised logical models that take these limitations of human reasoning abilities into account. “By fine tuning some elements of epistemic logic, I can make it sensitive to the reasoning of real people,” she says. Her key idea is that the resources available to a reasoner, such as time and working memory capacity, influence how well and in which depth she can reason. An agent’s level of experience might also influence her reasoning ability – a professor of set theory might reason better than a first-year student. Solaki built parameters into the models of epistemic logic that make them sensitive to these individual differences.

Thereby she implements an important idea from dual process theory, namely that reasoning according to explicit rules is effortful. Solaki’s approach highlights that humans are not either perfect reasoners or irrational dimwits. Instead, reasoning abilities depend on available resources, the quality of communication and the level of experience. “We need dynamic tools to account for how human reasoning evolves,” says Solaki. ”There is no reason that research in logic and psychology of reasoning have to be disjoint just because of some dogmatic understanding of what logic is.”

Read Anthi Solaki’s dissertation here.